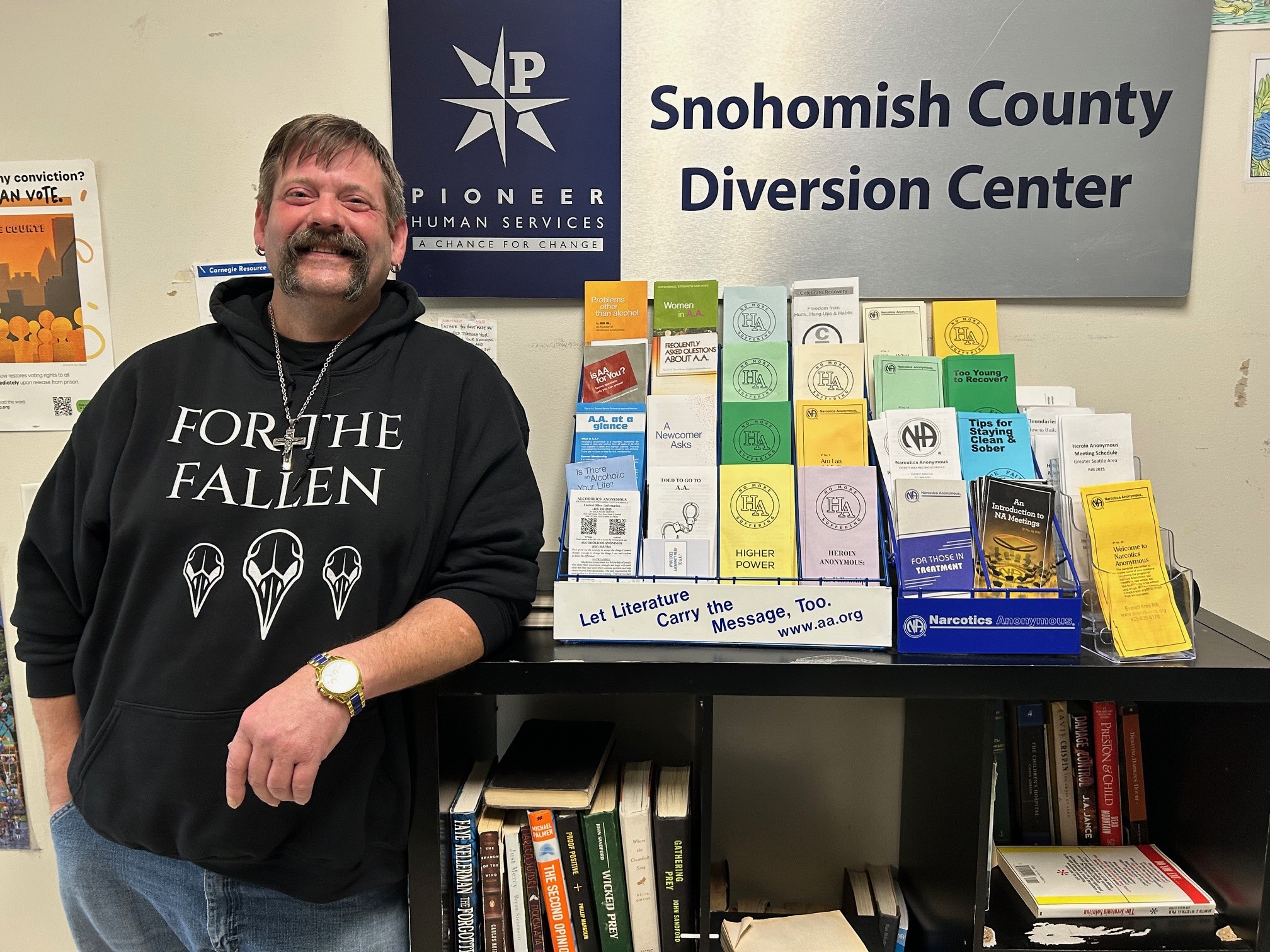

Treatment, Not Incarceration: Leroy’s Journey to Recovery

Leroy’s story is one of resilience, redemption, and the power of compassion paired with accountability.

Leroy (pictured) spent nearly three decades as a professional bull rider, traveling the rodeo circuit from the age of 13 until he was 41. Alongside that life, however, ran a long history of substance use and assault-related charges. By the time staff at the Carnegie Resource Center and the Snohomish County Diversion Center (SCDC) in Everett first met Leroy, he had been jailed 47 times in a three-year period for drug-related offenses and assault and battery.

His most recent jail stay lasted 45 days. When his probation officer saw no sustained effort to stay clean or change his behavior, Leroy was facing a six-month sentence.

Early Life and the Road to Addiction

Leroy had lived with his grandparents since he was six months old. At age 11, he lost his grandfather — the man who taught him to hunt and fish and served as his father figure and protector in Oklahoma. The loss was devastating and marked the beginning of Leroy’s downward spiral.

About a year later, while living with his biological mother and her boyfriend, Leroy experienced another profound trauma. His baby sister died from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). Leroy had been caring for her that evening and remembered kissing her goodnight and putting her to bed — only for her never to wake up. No one explained SIDS to him. As a child, Leroy internalized the guilt, believing he had done something wrong. Carrying that unspoken blame, he turned to harder drugs and eventually became involved with street gangs that offered him a sense of belonging.

Bull Riding: Talent and Turmoil

Despite the tragedy that shaped his childhood, Leroy discovered a talent for bull riding. He began riding large sheep, then started riding bulls at age 13. Soon, he was traveling the rodeo circuit.

The sport was thrilling but brutal, and Leroy battled addiction throughout his career. Drugs helped calm his nerves before a ride and dull the pain afterward. Over the years, he suffered countless injuries and broken bones, often climbing back onto a bull before fully healing.

“That’s where the term ‘cowboy up’ comes from,” Leroy said. “You just get up and climb on again.”

A Move and a Breaking Point

“I had a ranch and a life in Oklahoma,” Leroy shared. “I gave up hard drugs in 2017, but I was still drinking and smoking weed. My mental health was suffering. There were moments when I seriously considered suicide — with a gun to my head.”

In 2019, hoping for a fresh start, Leroy reconnected with a former high school girlfriend in Washington and moved. At first, things seemed to improve. He found work and stability — until he realized she was still using hard drugs. He left quickly, but the cycle continued.

In Snohomish County, Leroy found himself repeatedly in and out of jail due to drinking and related behavior.

A Choice: Jail or Recovery

“I was sick and tired of the drugs and the revolving jail door,” Leroy said. “After my last 45-day jail sentence, I was now facing six more months. My PO asked if I’d ever considered staying clean. I said, ‘Why?’ But I knew I couldn’t go back to jail. I was done. My way wasn’t working.”

His probation officer offered him a choice: serve the sentence or enter a diversion program and treatment. Leroy didn’t hesitate.

“My PO said if I was serious, she’d push it through ASAP — and I agreed,” shared Leroy

Leroy was immediately referred to the Carnegie Resource Center and shared his need to get in a diversion program. Rebecca Nelson, the current Carnegie director, met with Leroy and discussed the diversion program requirements. Rebecca then called the Snohomish County Outreach Team (SCOUT), a program that works to reduce reliance on incarceration by connecting people to housing, treatment, and critical resources through trust and engagement.

Leroy’s SCOUT social worker, Calei Vaughn (a former director of the Carnegie Resource Center) quickly arranged for his assessment. Once cleared, she took him directly to the Snohomish County Diversion Center (SCDC) where he was admitted that day,

Leroy encountered consistent compassion, structure, and guidance.

Building Stability and Purpose

At SCDC, Leroy worked closely with his case manager, Scott Rowley, who spoke with him daily. Leroy engaged fully in Intensive Outpatient Treatment (IOP) and outpatient counseling, secured clean and sober housing, found part-time construction work, and attended four in-person recovery meetings each week at his residence.

With stable housing and a strong foundation in recovery, Leroy felt ready to look forward.

Recovery, Education, and Leadership

Determined to help others, Leroy pursued education to become a recovery coach. He enrolled in Recovery Café training programs, completing courses in ethics, professionalism, advocacy, and emergency department coaching. He earned 70 college credits and began building a future rooted in service.

A few years later, the clean and sober house where Leroy lived offered him a house manager position in Marysville. In 2025, he was promoted to house manager on the Tulalip Reservation — a role that held personal meaning, as Leroy is half Native.

“I love this role,” Leroy said. “I want to learn more about Native ways and their Wellness Court — a Native version of Drug Court. Every day, I try to be a role model. I want others to see my recovery and believe it’s possible for them too. I don’t judge. I always tell my residents to come talk to me anytime.”

A Full Circle Moment

Today, when local police encounter Leroy, they’re stunned by the transformation. This is the same man they once arrested nearly every month. Now, Leroy runs multiple clean and sober meetings and partners with SCDC, welcoming current diversion clients to attend. He openly shares his own journey through the program and how recovery changed his life.

“I want them to see my success,” Leroy said. “I can tell when someone is really struggling. One day, I hope to work in a hospital emergency room with patients who’ve overdosed or are battling addiction. Many medical professionals don’t understand addiction and detox — I want to be a professional advocate for recovery.”

Leroy closed with this reflection:

“I’m an addict – a former addict. But there are good professionals out there who want to help — not judge. I have met many amazing professionals through Pioneer’s SCDC and the Carnegie Resource Center; and through SCOUT, and the clean and sober housing organization where I manage a house. Now, I’m in an amazing position to help others by sharing what I’ve learned.”